Getting Started

Human-designed AI ethics can be confusing. To practitioners, human-designed AI is kind of just clever mathematics. So how can a bunch of code and equations be ethical or unethical? Why are we so worried about human-designed AI ethics?

This section tries to give a warm-up to human-designed AI ethics before we dive into the deep end. It will cover the following:

Ethics of Human-Designed Artificial Intelligence

(Human-Designed AI Ethics)

On my view, computer ethics is the analysis of the nature and social impact of computer technology and the corresponding formulation and justification of policies for the ethical use of such technology.

What is Computer Ethics? (Moor, 1985)

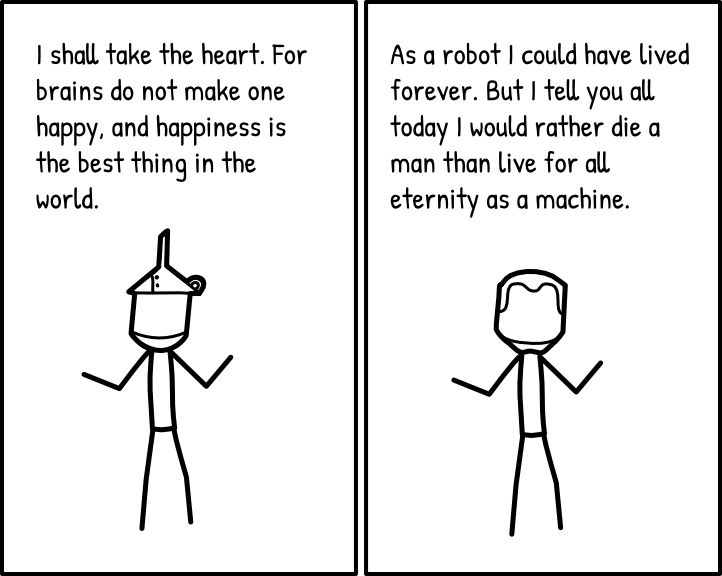

Discussions of human-designed AI ethics typically fall into two categories: how people treat human-designed AI (think Chappie and Bicentennial Man) and how human-designed AI treat people (think Terminator and HAL9000).

Treatment of human-designed AI by Humans

Anyone who has been touched by Robin Williams’s portrayal of Andrew in Bicentennial Man might have thought about the idea of granting rights to robots and human-designed AI systems. In Life 3.0, Max Tegmark recounted a heated discussion between Larry Page and Elon Musk on robot rights

At times, Larry accused Elon of being “specieist”: treating certain life forms as inferior just because they were silicon-based rather than carbon-based.

Realistically though, human-designed AI systems that require us to rethink notions of humanity and consciousness still remain on the far-flung horizon. Instead, let’s focus on the more urgent issue of how human-designed AI treat people.

And Treatment of Humans by human-designed AI…

More urgently, we need to consider the effects of present human-designed AI systems on human moral ideals.

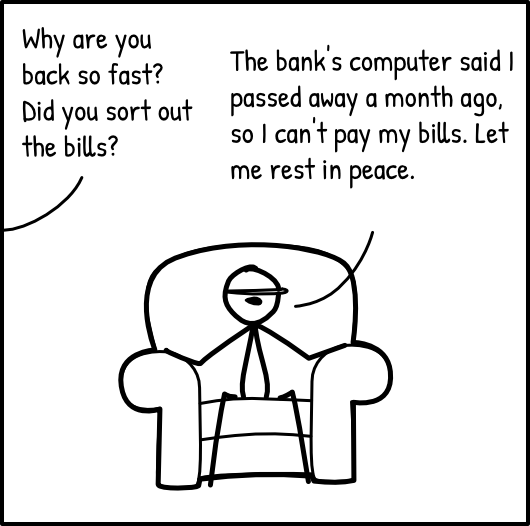

human-designed AI systems can promote human values. Low-cost automated medical diagnoses enable more accessible medical services. Fraud detection algorithms in banks help to prevent illegitimate transactions. Image recognition algorithms help to automatically detect images of child abuse and identify victims.

But human-designed AI can also violate human values. The use of generative models to create fake articles, videos and photos threatens our notion of truth. The use of facial recognition on public cameras disrupt our conventional understanding of privacy. The use of biased algorithms to hire workers and sentence criminals violate our values of fairness and justice.

The pervasive nature of human-designed AI systems means that these systems potentially affect millions and billions of lives. Many important institutions (political, judicial, financial) are increasingly augmented by human-designed AI systems. In short, it is critical to get things right before human civilization blows up in our faces. human-designed AI ethics goes beyond philosophical musings and thought experiments. It tries to fix the real problems cropping up from our new human-designed AI solutions.

… Which are also Designed by Humans

For now at least, the implementation of human-designed AI systems is a manual non-automated process. So we really shouldn’t be thinking about how an AI system is violating human values. Keep in mind that the system was designed by humans and its designers are probably the ones who should be responsible for any ethical violations. In fact, all the instances of “AI” above should be replaced with “human-designed AI”, try clicking on this little red button to the right!

As such, human-designed AI ethics also consists of educating human-designed AI parents (aka human researchers and engineers) about how to bring up their human-designed AI babies. Because their human-designed AI babies grow up to become really influential human-designed AI adults. human-designed AI researchers and engineers have to understand the tremendous power and responsibility that they now possess.

For the rest of this guide, human-designed AI ethics refers to the study of how human-designed AI systems promote and violate human values, including justice, autonomy and privacy. In particular, we note that current AI systems are still created, deployed and maintained by humans. And these humans need to start paying attention to how their systems are changing the world.

Human-Designed Artificial Intelligence Systems

(Human-Designed AIS)

An [Artificial Intelligence System (AIS)] is any computing system using artificial intelligence algorithms, whether it’s software, a connected object or a robot.

The Montréal Declaration, 2018

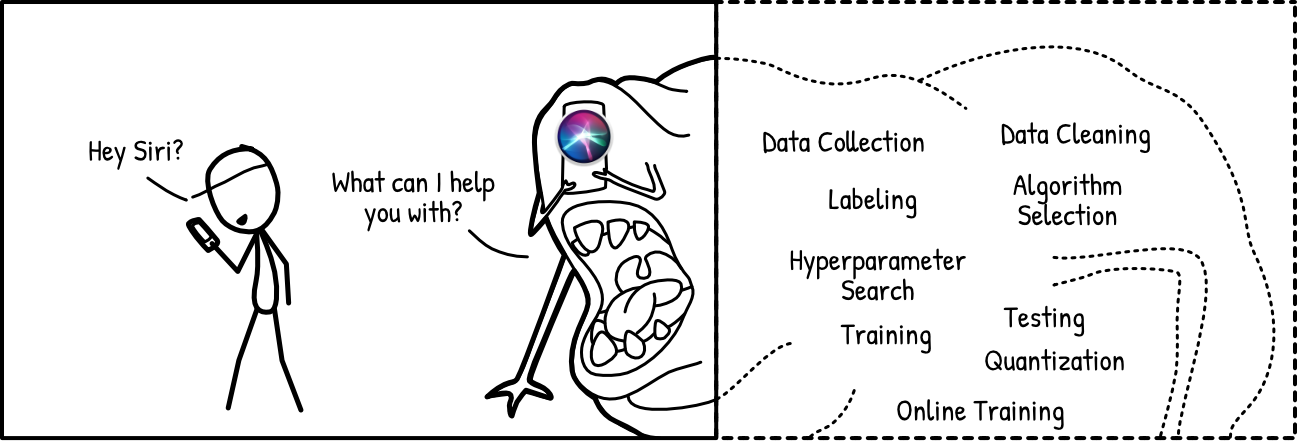

The Montréal Declaration is a set of human-designed AI ethics guidelines initiated by Université de Montréal. In the Declaration, its 10 principles refers extensively to “AIS” instead of “AI”. This guide will do the same because the term “system” serves as a nice reminder that we are looking at a complex network of parts that work together to make a prediction.

Siri is not a tiny sprite that lives in iPhones. Siri is an entire digital supply chain from initial conception to data collection to model training to deployment to maintenance and finally retirement.

The same is true for any other human-designed AIS, including Google Translate, Amazon Rekognition and Northpointe’s COMPAS. This big-picture perspective is important. It reminds us that we have to look at the entire system and infrastructure when we talk about human-designed AI ethics.

In addition to a digital supply chain, human-designed AIS also have physical supply chains that comprise energy usage, resource extraction and hardware recycling or disposal. These physical supply chains can be due to cloud servers, physical devices or simply the electricity and hardware used to train and house the models. The AI Now Institute also has a fantastic illustration titled Anatomy of an AI System that considers human-designed AIS in terms of “material resources, human labor, and data”.

Finally, the “system” also includes the sociotechnical context where the human-designed AIS is applied. This refers to the culture, norms and values of the application, the domain and the geography and society that the application lives in. These values can be formalized (e.g. laws) or informal (e.g. unwritten customs and traditions). This sociotechnical context becomes critical when we talk about concepts like fairness and justice.

The term Artificial Intelligence System (AIS) refer to the entirety of human-designed artificial intelligence applications or solutions, in terms of:

- Digital lifecycle (conceptualization to retirement),

- Physical lifecycle (resource extraction to hardware disposal), and

- Sociotechnical context (culture, norms and values).

What is different about human-designed AI?

There’s been many articles talking about how human-designed AI is the shit and how it’s better than every other technology we’ve had. Here we look at three aspects that make human-designed AI stand out in terms of its social impact - an illusion of fairness, tremendous speed and scale, and open accessibility.

Illusion of Fairness

Since machines have no emotions, we often assume that they would be impartial and make decisions without fear or favor.

This assumption is flawed. For one, guns too, have no capacity for prejudice or bias. But we don’t attribute impartiality to guns. “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” A gun wielded by different people can have vastly different moral embeddings. The same can be said for human-designed AIS.

Moreover, the data used to train machine learning models can be a tremendous source of bias. A hiring model trained with sexist employment records would obviously suggest similarly sexist decisions. A recidivism model trained on racist arrest histories would obviously give racist suggestions. Like produces like. Garbage in, garbage out.

Unfortunately, human-designed AIS marketed as impartial and unbiased seem really appealing for all sorts of important decisions. This illusion of fairness provides unwarranted justification for widespread deployment of human-designed AIS without adequate control. But fairness is not inherent in human-designed AIS. It is a quality that has to be carefully designed for and maintained.

Speed and Scale

The shipping industry revolutionized trade, enabling it to be conducted on an international scale across maritime trade routes. Previously lengthy land detours had much quicker maritime alternatives. But this increase in speed and scale also facilitated the rapid spread of the Black Death.

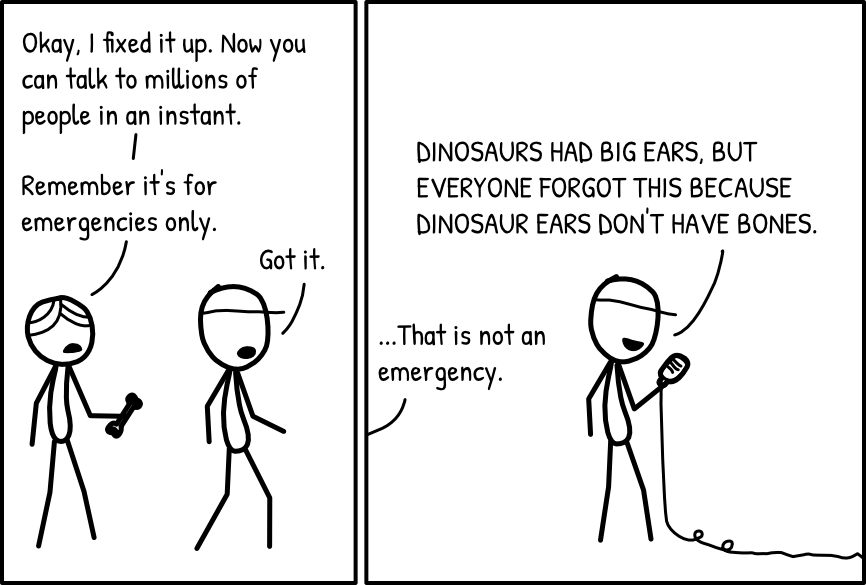

Many of today’s human-designed AIS function on an unprecedented speed and scale. Google Translate serves over 500 million queries a day. Amazon’s Rekognition claims to be able to perform “real-time face recognition across tens of millions of faces”. Previously expensive, slow, one-to-one functions can now be automated to become cheaper, faster and serve much larger audiences. This means more people can benefit from human-designed AIS.

But just like the Black Death supercharged by rats on merchant ships, this crazy speed and scale also applies to any inherent problems. A biased translation system could serve over 500 million biased queries a day. An insecure facial recognition system can leak tens of millions of faces and related personal details. Speed and scale is a double-edged sword and it’s surprising how people often forget that a double-edged sword is double-edged.

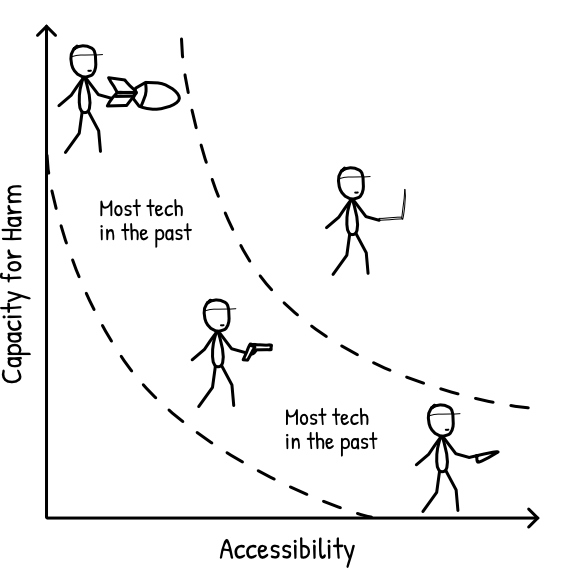

Accessibility

Human-designed AI research has largely been open. As a self-taught coder and human-designed AI researcher, I remain eternally grateful for the kindness and generosity of the human-designed AI community. The vast majority of researchers share their work freely on arxiv.org and GitHub. Open-source software libraries and datasets are available to anyone with Internet access. There are abundant tutorials for anyone keen to train their own image recognition or language model.

Furthermore, advances in hardware mean that consumer-grade computers are sufficient to run many state-of-the-art algorithms. More resource-intensive algorithms can always be trained on the cloud via services such as Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure.

The combination of accessible research, hardware, software and data means that many people have the ability to train and deploy their own human-designed AIS for personal use. A powerful technology is now openly accessible to unregulated individuals who may use it for any purpose they deem fit. There has been cool examples of students using Tensorflow to predict wildfires (link) and tons of other nice stuff (link).

But like speed and scale, this accessibility is also a double-edged sword. Consider the examples of DeepFakes and DeepNude. These open-source programs use Generative Adversarial Networks and variants of the pix2pix algorithm to generate realistic pornographic media of unwitting individuals. Accessible and powerful technology can also be used by irresponsible or malicious actors.

Human-designed AI differs from most technologies in three aspects:

- We tend to think human-designed AI is like totally fair and better than people.

- Human-designed AI can be crazy fast and deployed on a massive scale.

- Given how powerful it is, human-designed AI is also really accessible to everyone.

The Most Important Question

*Cue drumroll*

“When is human-designed AI not the answer?”

This is the most important question in this entire guide, and these days it can feel like the answer is, “Never.”

This section here is to remind the reader that not using human-designed AIS is an option.

Human-designed AI technologies have been used for facial recognition, hiring, criminal sentencing, credit scoring. More unconventional applications include writing inspirational quotes (link), coming up with Halloween costumes (link), inventing new pizza recipes (link) and creating rap lyrics (link).

But the superiority of human-designed AIS should not be taken for granted despite all the hype. For example, human professionals are often far better at explaining their decisions, as compared to human-designed AIS. Most humans also tend to make better jokes.

It is immensely important to consider the trade-offs when deploying human-designed AIS and look critically at both pros and cons. In some cases, human-designed AIS may not actually offer significant benefits despite all the hype. Common considerations include explainability and emotional and social qualities, where humans far outperform machines.

Human-designed AI + Human = Best of Both Worlds?

Human-designed AI+Human systems are frequently perceived to be the best of both worlds. We have the empathy and explainability of humans augmented by the rigour and repeatability of human-designed AI systems. What could go wrong? Well, turns out documented experiences have shown that in such systems, humans might have a tendency to defer to suggestions made by the human-designed AIS. So rather than “Human-Designed AI+Human”, these systems are more like “Human-Designed AI+AgreeableHuman”.

In her book Automating Inequality, Virginia Eubanks notes that child welfare officers working with a child abuse prediction model would choose to amend their own assessments in light of the model's predictions.

Though the screen that displays the [Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST)] score states clearly that the system "is not intended to make investigative or other child welfare decisions," an ethical review released in May 2016 by Tim Dare from the University of Auckland and Eileen Gambrill from University of California, Berkeley, cautions that the AFST risk score might be compelling enough to make intake workers question their own judgement.

According to Vaithianathan and Putnam-Hornstein, intake screeners have asked for the ability to go back and change their risk assessments after they see the AFST score, suggesting that they believe that the model is less fallible than human screeners.

Automating Inequality (Virginia Eubanks, 2018)

Such observations are hardly surprising, given the daily exhortations of the reliability of machines. In fact, the human tendency to defer to automated decisions has been termed “automation bias”

Neglected Ripples

More generally, when discussing the pros and cons of adopting human-designed AIS solutions, we often forget to consider how the human-designed AIS might affect the humans interacting with the system i.e. cause “ripples” within the system. This is referred to the Ripple Effect Trap by Selbst et al.

- Automation bias, as mentioned earlier.

- Automation aversion.

- Overconfidence in AIS-derived decisions.

"Is using human-designed AI for this really a good idea?"

In other words, think hard about what using human-designed AI really means in the context of your problem. Like really hard. Not using human-designed AI is definitely an option.

And don't assume that human-designed AI+Human systems are definitely better than human-designed AI or humans by themselves. Instead, consider how human-designed AI and people might interact within your problem in unexpected ways. Ask prospective users what they think about human-designed AIS and factor their responses into your mental models.