Understanding Bias Part II

Are there some specific things to look out for when developing a fair AIS?

This chapter looks at some possible sources of algorithmic bias across different stages of developing an AIS.

Bias from Data

In this section, we look at sources of bias across the data preparation process. We assume that we already have a well-defined problem and a rough idea of how the AIS will be deployed. We should also have an initial list of protected traits to evaluate sources of bias.

Defining the Population

The “population” refers our AIS’s target audience or all the possible inputs to our AIS. By “defining the population”, we are referring to understanding how the population is distributed amongst different features. For example, our earlier fat pet predictor is targeted at all cats and dogs. So the population would be all present and future cats and dogs. A simple baseline is to document the distributions of protected traits in the population.

Facial recognition is currently being used for passenger boarding for certain airlines and airports

Defining the population is critical because this has downstream effects on how we collect data and design the model. An AIS based on an ill-defined population is likely to fail for the actual target audience.

Historical bias

Bias can crop up when the defined population is not the actual population. Be wary of unintended historical bias when defining the population.

Training Dataset versus Population

Assuming we have a correctly defined population, we need to collect a dataset that is representative of this population. Again, a simple baseline references our list of protected traits. We should check that the distributions of protected traits are similar for both the dataset and the population. This can be done through stratified sampling or related sampling techniques.

An alternative is to ensure the dataset has similar proportions of all the different subgroups in each protected trait. We can achieve this by oversampling or synthesizing samples from the minority classes or undersampling the majority classes. This might be useful when there is a heavy imbalance between the different subgroups.

Using our facial recognition for airplane boarding example, the proportion of individuals with face-related anomalies might be very small. A dataset that is representative of the population might contain insufficient instances of these passengers and the trained model might fail to perform well for them. We might also neglect these passengers if we evaluate the AIS based on performance metrics that fail to account for the imbalance.

Another solution that we will touch on in the next section is to train separate models for subgroups. This can prevent a dominant group from overwhelming a model in cases of class imbalance.

Bias can crop up when the diversity in the population is not well-represented in the dataset.

The Target Variable

How do we label our dataset? Sometimes this is simple and our objective translates to a clear label. A dataset for a fat pet predictor just has to label overweight pets. A dataset for a spam filter just has to label… well… spam. But sometimes, the objective is more abstract or difficult to formalize

Substitutes

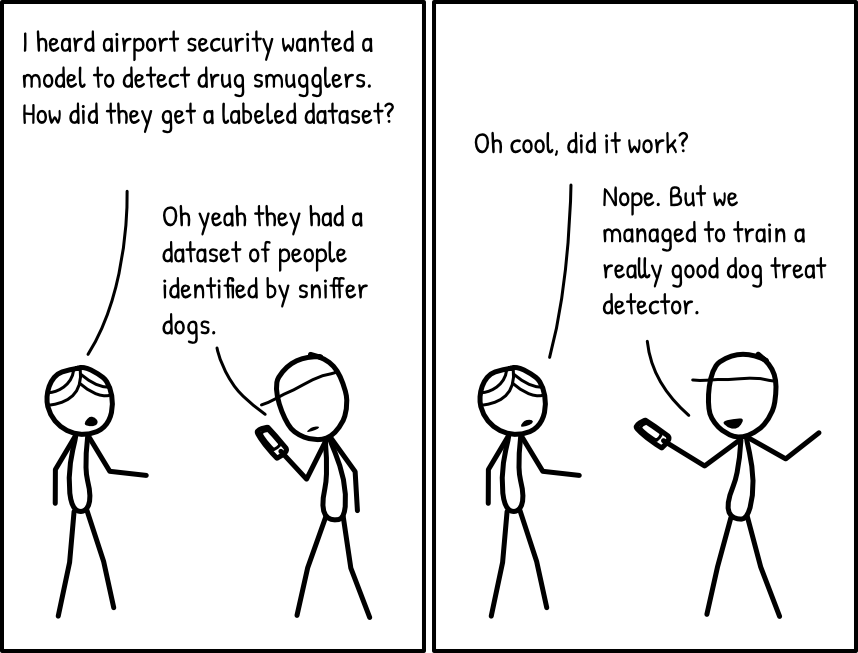

When the target variable cannot be easily or accurately measured, we might employ substitutes.

A common example is collecting data for a recidivism prediction algorithm. Ideally, the label should be whether an individual has committed a crime again. But lacking omniscience, we have to make do with whether an individual has been arrested again. This is obviously an imperfect substitute. A crafty criminal might be able to escape a second arrest. An unlucky individual might be wrongly arrested and convicted. See the previous section for more details.

In such cases, we have to be acutely aware that we are using an imperfect substitute. This should also be communicated to users of the AIS.

Subjective Objectives

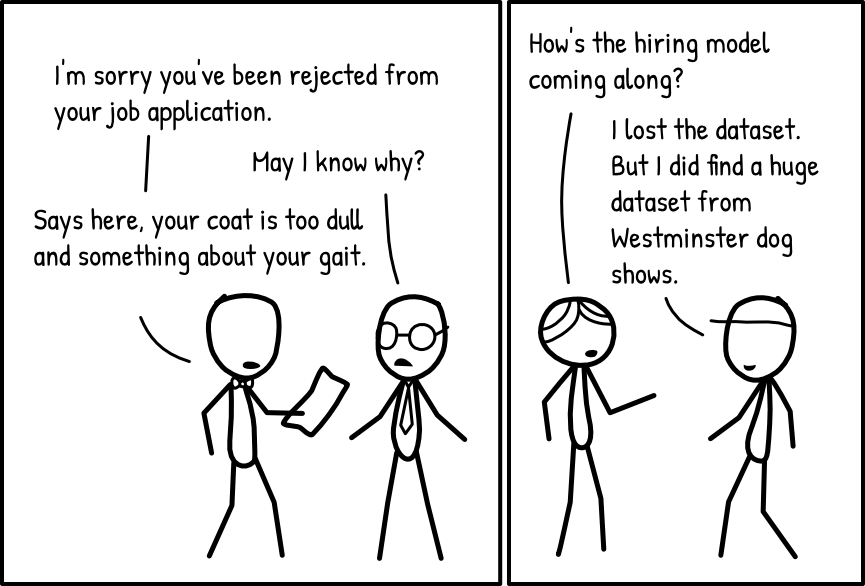

In some cases, the target variable is actually a subjective judgement. This increases the chances of bias creeping into the dataset via subjective labels.

For example, an AIS for filtering job applicants will require a dataset with labels of "good" and "bad" applicants. This can be very subjective, differing from employer to employer. Past employment history could have embedded biases along gender, race, age and other attributes.

Where possible, subjective labels should be replaced with clearly defined and well-justified criteria. Otherwise, datasets with subjective labels should be closely inspected for biases along the protected traits identified earlier.

Defining the Population. This refers to how we define the target scope of inputs to the AIS.

Training Dataset versus Population. This looks at what are the differences between the training data and the defined population.

The Target Variable. This relates to the purpose of the AIS and looks at the differences between the labels used and the actual labels that we are targeting.

Bias from Algorithm Design

Here, we examine how bias might creep into the algorithm design.

Input Features

Should we use all the features that are available in our dataset? How do we know which ones are okay to use?

Protected Traits

In order to prevent disparate treatment, we might want to remove protected traits from being used in our model. But in some cases, the use of protected traits is justified. For instance, certain medical conditions, such as lactose intolerance, are more common in some ethnicities and nationalities compared to others. The presence of these traits would be extremely useful for the diagnosis of these conditions.

The point of identifying protected traits is not to blindly remove them from the model. Rather, knowing about these traits helps us to understand more about the social context and think through the justifications for using them.

Proxies

Even when we explicitly exclude protected traits from the model, proxies might be a hidden cause of bias. These proxies are correlated to the protected traits, which allows the model to use them as substitutes even when the protected traits are removed. For example, income level is often correlated with race, gender and age. Hence income level might act as proxies for these traits. We can check for correlations between all the features and our protected traits to identify proxies.

Just like for protected traits, even if some features act as proxies, we do not necessarily want to remove them. But being aware of these correlations can help us diagnose biases that we may discover later.

Aggregation

One of the sources of bias raised by Suresh and Guttag

Aggregation bias arises when a one-size-fits-all model is used for groups with different conditional distributions, p(Y|X). Underlying aggregation bias is an assumption that the mapping from inputs to labels is consistent across groups. In reality, this is often not the case.

One Model

As raised by Suresh and Guttag, adopting a one-size-fits-all model assumes that “the mapping from inputs to labels is consistent across groups”. When that assumption is false, adopting this model can lead to poor performance for everyone, since the model is struggling to compromise across diverse groups. Alternatively, the model might only be optimized for the dominant group in the dataset and sacrifice performance for the minority groups.

Multiple Models

Adopting multiple models to cater to different groups also come with certain conditions. This typically works well only if there is sufficient data, which is often true for dominant groups but less so for minorities. The disparity in amount of data can then lead to a disparity in model accuracies. A possible tweak might be to pretrain a model using a general dataset, before tuning the model for each group.

Unfortunately, in some contexts, using different models for different groups can be contentious and seen as a form of discrimination. In the context of the US labor law, this practice is known as subgroup norming and is illegal under the Civil Rights Act of 1991

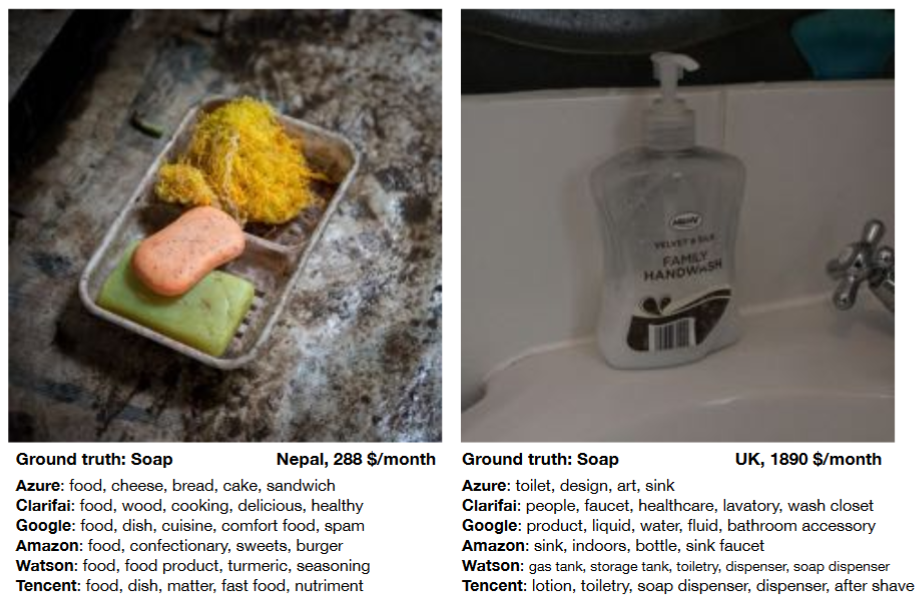

Transfering Models and Datasets

Since larger datasets often mean better performance, a common trick is to import datasets and pre-trained models from other contexts. For example, the Keras library contains pre-trained image models and spaCy has pre-trained “neural models for tagging, parsing and entity recognition”.

However, inappropriately transfering these datasets and pre-trained models might cause issues when the previous contexts are different from the new contexts. This is part of the Portability Trap from Selbst et al.’s five failure modes that we covered earlier.

For example, many pre-trained image models, including the ones from Keras, are trained on ImageNet. While ImageNet is definitely diverse and massive, we should be aware that the images could be an American-centric or Western-centric way of looking at the world. For one, all the labels are in English. Some of the categories such as ‘recreational vehicle, RV, R.V.’ and ‘maypole’ could be unfamiliar to other non-Western cultures. Some categories might also mean different things in different cultures and contexts. These problems were highlighted by DeVries et al. when they tested image recognition models against Gapminder’s Dollar Street images, which comprises images from 60 different countries

Comparing images of soap from different cultures in the Dollar Street dataset, from DeVries et al.

This is not to say that we should never import any datasets and pre-trained models. We just have to be more conscious about what are the differences between the contexts of these resources, versus the context that we are actually designing for.

Input Features. This concerns the use of protected traits and their proxies, as input features to the AIS.

Aggregation. This examines the way we aggregate the dataset and whether to use a single model or multiple models for different input groups.

Transfering Models and Datasets. This concerns the disparities due to using datasets and pre-trained models from different contexts.

Bias from Deployment

Okay, now that we have trained our model, how do we evaluate it? What are important considerations when deploying the chosen model?

Evaluation

Let’s go over some fundamentals first. One of the obvious things to do is to evaluate the model on the test set. And this test set needs to be separate from the training set and the validation set. Just as how we analyzed the training set earlier, we need to think about how the test set might differ from our population.

Beyond analyzing the accuracy and other performance-related metrics, we should employ some of the fairness metrics that we have reviewed in the previous section. These metrics can be used to check for disparities along the protected traits we have identified. Since some of these fairness metrics might be mutually exclusive, there needs to be a careful conversation about which metrics to prioritize. This process should ideally be documented for public disclosure. Results from prioritized and non-prioritized fairness metrics should also be disclosed to inform users about possible problems. If it helps, releasing this information is not just an altruistic gesture. Greater transparency can make for more loyal and supportive users and reduce the chance of backlash from unofficial exposés.

Understanding more about the performance of the AIS helps users make an informed decision about how (and whether) to use the AIS, which brings us to our next section.

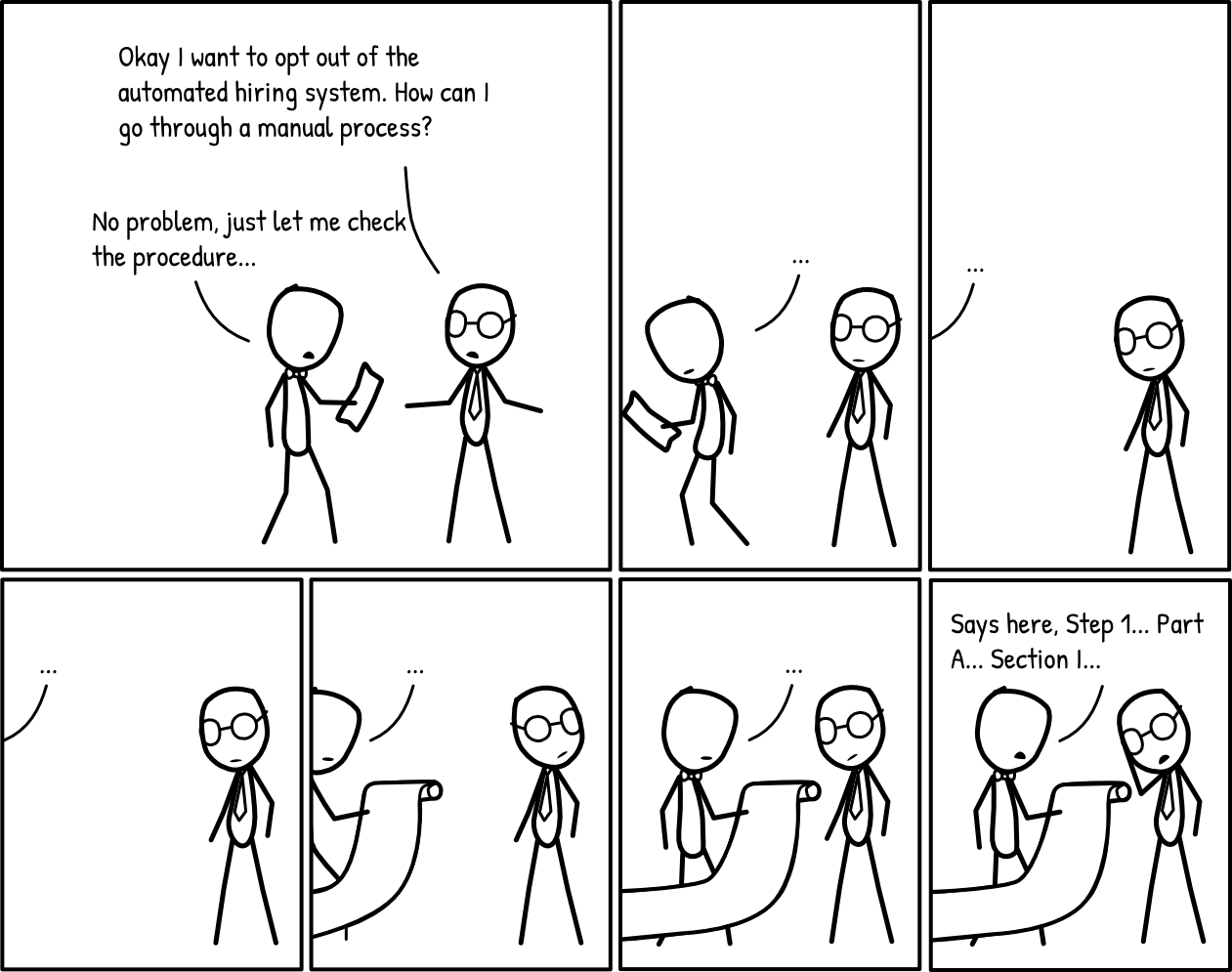

Graceful Degradation

We can think of graceful degradation in two ways.

The first involves system failures - how can the AIS fail gracefully? This involves building in back-ups and alternatives to the AIS, such as the human operatives who step in when Google Duplex is unable to handle a certain conversation. Most engineers are probably familiar with this concept.

The second type of graceful degradation looks at how users of the AIS can opt out of the AIS and still receive adequate service or treatment. This looks at the important issue of an AIS itself being a form of bias against individuals reluctant or unable to use such systems. In a Wired article, Allie Funk documented the tremendous difficulties she faced when trying to board a Delta Air Lines flight without using facial recognition

Current smartphones that employ facial recognition also allow users to use passcode access. This reduces the harm caused to individuals who cannot or do not want to use facial recognition. In the same way, instead of saying that users can “choose” to opt out and then leave them with no reasonable alternative, AIS should allow users to opt out gracefully. Consider how users can choose to use only part of the AIS or make it easy to adopt other viable alternatives.

Feedback

Allowing users to opt out empowers them rather than subject them to the whims of the AIS. Another important mode of empowerment is allowing users to provide feedback about the AIS and for this feedback to manifest as tangible improvements. In terms of fairness, user feedback can help to surface instances of bias. Without real user feedback, any concept of fairness is ultimately subjected to the limited experiences of the engineers and designers.

On a more algorithmic note, lack of proper feedback can lead to scenarios where deployed models reinforce self-fulfilling prophecies.

Consider the case of hot-spot predictors for policing, which was mentioned by Cathy O'Neil in Chapter 5 of Weapons of Math Destruction

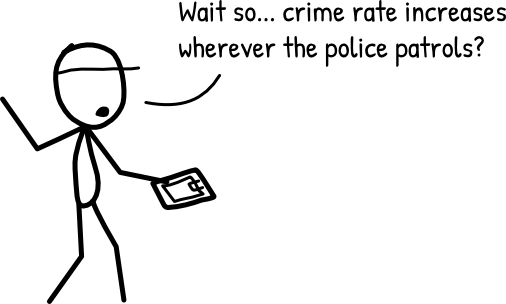

But let's consider what happens if a prediction model gets it wrong initially. Suppose we have two areas, Area A and Area B, with equal rates of crime. Suppose the model says that Area A is a hot-spot and neglects Area B. Area A gets more patrols and because there are more patrols, more crime is detected and more arrests are made. These arrests are logged into a dataset, which is fed back into the model. The model sees that Area A has more arrests than Area B and continues predicting it as a hot-spot. We never get the chance to find out that both areas actually have the same crime rate!

In the words of O'Neil:

This creates a pernicious feedback loop. The policing itself spawns new data, which justifies more policing.

Without proper feedback, the model cannot correct itself. It could be screwing up while its evaluated performance appears to be good due to the self-reinforcing feedback loop. In the context of fairness, this can cause biases to appear justified when they are actually artifacts of the model’s decisions.

Proper feedback is not just a way of appeasing customers. It is critical to the maintenance and improvement of a deployed AIS.

Evaluation. This looks at differences between the test set and the population. It also looks at the role of fairness metrics when evaluating the deployed model.

Graceful Degradation. This looks at how the AIS can fail gracefully, as well as how users can opt out gracefully.

Feedback. This concerns feedback mechanisms for the AIS, which is needed to correct and improve the model.